For most of my life, I have served as a “party prop” to some people – something they can show off to friends. I’m the daughter of a former NBA star and have an education and good manners. Some people view me like a novelty act, a show pony.

When my family and I first moved to Charlotte in 1990, my mom asked a young, white woman – a flight attendant – to be my babysitter. This woman felt like part of our family. She was indebted to my grandparents for giving her a place to stay and became “friends” with my mother. What an interesting twist on “The Help,” the book and movie emblematic of the Old South, where white people claimed to love their hired help like family, all the while making them use an outhouse. As I grew older, I realized something about my first babysitter. She didn’t really love us like family. She liked the idea of being associated with us. We weren’t aware of it then, but we were her token Black family.

According to the Oxford dictionary, tokenism is “the practice of making only a perfunctory or symbolic effort to do a particular thing, especially by recruiting a small number of people from underrepresented groups in order to give the appearance of sexual or racial equality”.

For our former babysitter, this meant the casual name drop of my Dad for any reason that better served her, whether it was securing a gig as a photographer for the ACC Men’s Basketball Tourney or scoring his latest children’s book for her daughter, but disappearing when my boyfriend and I were stranded from a trip due to inclement weather.

Now in her 50s and still working at the airline, she was recently caught on film at her workplace ignoring the requests of people of color, being curt and using racial slurs along with stereotypical tropes toward people of color. When the recording went viral, she called my Mom to remind her “black sister” (her words) that she loves us and that this was all a big misunderstanding. None of us were all that shocked. Upon reflection, I realized in the 20 plus years of knowing her, we were the only black “friends” she affiliated with, unless it was another black celebrity family.

Seeing her in that video reaffirmed some of my worst fears that deep down all white people think this way and there will never be true equality. Even worse, and color aside, someone can pretend to care for you but genuinely only value you for what you can do for them. I’ve known since I was little that black professional athletes – and by extension, their families – are accorded status by white people that isn’t granted to all people of color. I remember as a child at the age of 8 and knowing something was different –because there was a certain twinkle in some eyes when they knew I was connected to the iconic SpaceJam Monstar that adversely dimmed when I purposely would say my dad had some odd profession.

I am a Black woman, but I am also the daughter of status. Growing up, I was often told: “You’re different. You’re not “Black Black” or “You’re pretty … for a black girl.” Or, “You even ‘talk white.’”

Imagine what Black people who aren’t sports stars – or their family members – have to do to get ahead.

In business, successful Black people often come up against the tokenism label. It’s not enough that we tamp down our Blackness. But when we do rise through the ranks, we get criticized for being handed a job just to tick a box.

We know what gets said about us.

What must we do to prove we deserve the promotion? I don’t use my Blackness as a marketing strategy. I don’t think anyone should hire me or my company because I am Black. They should hire me because I am really good at what I do. As a double minority, I know about feeling like a “token.”

As Black women, Kamala Harris and I are both double minorities. I don’t know how she feels about it, but I can tell you I have to always be on my best behavior. I know there will always be people who watch me closely, wondering if I’ll reveal myself to be undeserving of success.

I think I know what Arthur Ashe – another famous Black professional athlete – must have felt. As the only Black person on the professional tennis circuit, he had to be unfailingly polite. John McEnroe could throw temper tantrums, but Arthur Ashe had to be ever the gentleman.

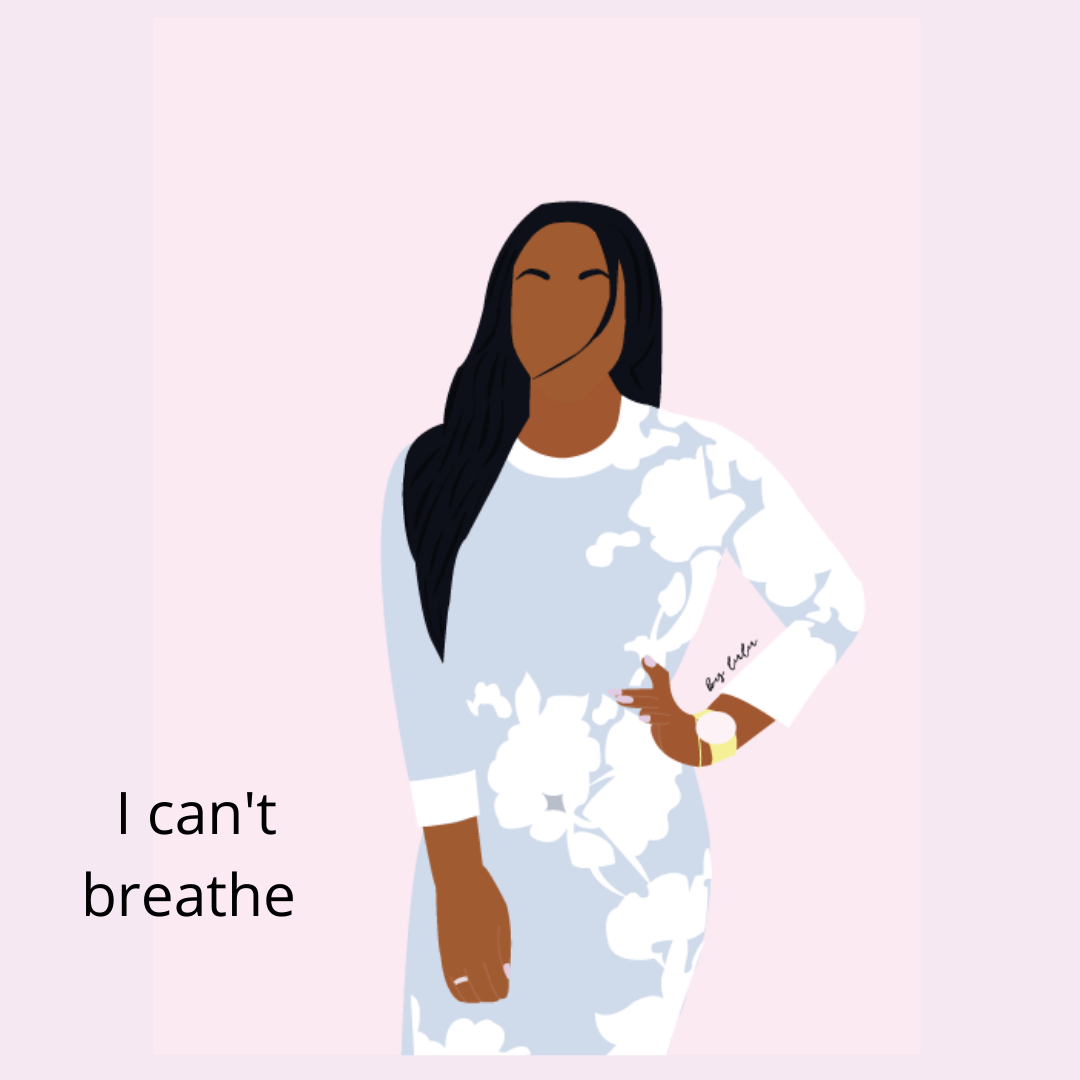

The Black Lives Matter movement is, first and foremost, about saving Black lives from police brutality. But, it’s also about abolishing the notion of tokenism. Yes, we’re demanding justice for Walter Wallace Jr, Breonna Taylor and all the other countless victims of police brutality. But we’re also cheering for Kamala. We’re mad, but we’re finding reasons for hope.

We are saying to the police: Stop killing us.

We are saying to management and co-workers: Stop underestimating us and stop thinking the only way we get ahead is when we’re handed something.

We are saying to former babysitters and countless others like her: Stop seeing us as tokens.